By William M. Noall, Esq. | January 5, 2026

I want to share something we’ve learned the hard way over the years—something that’s cost estates real money until we figured it out.

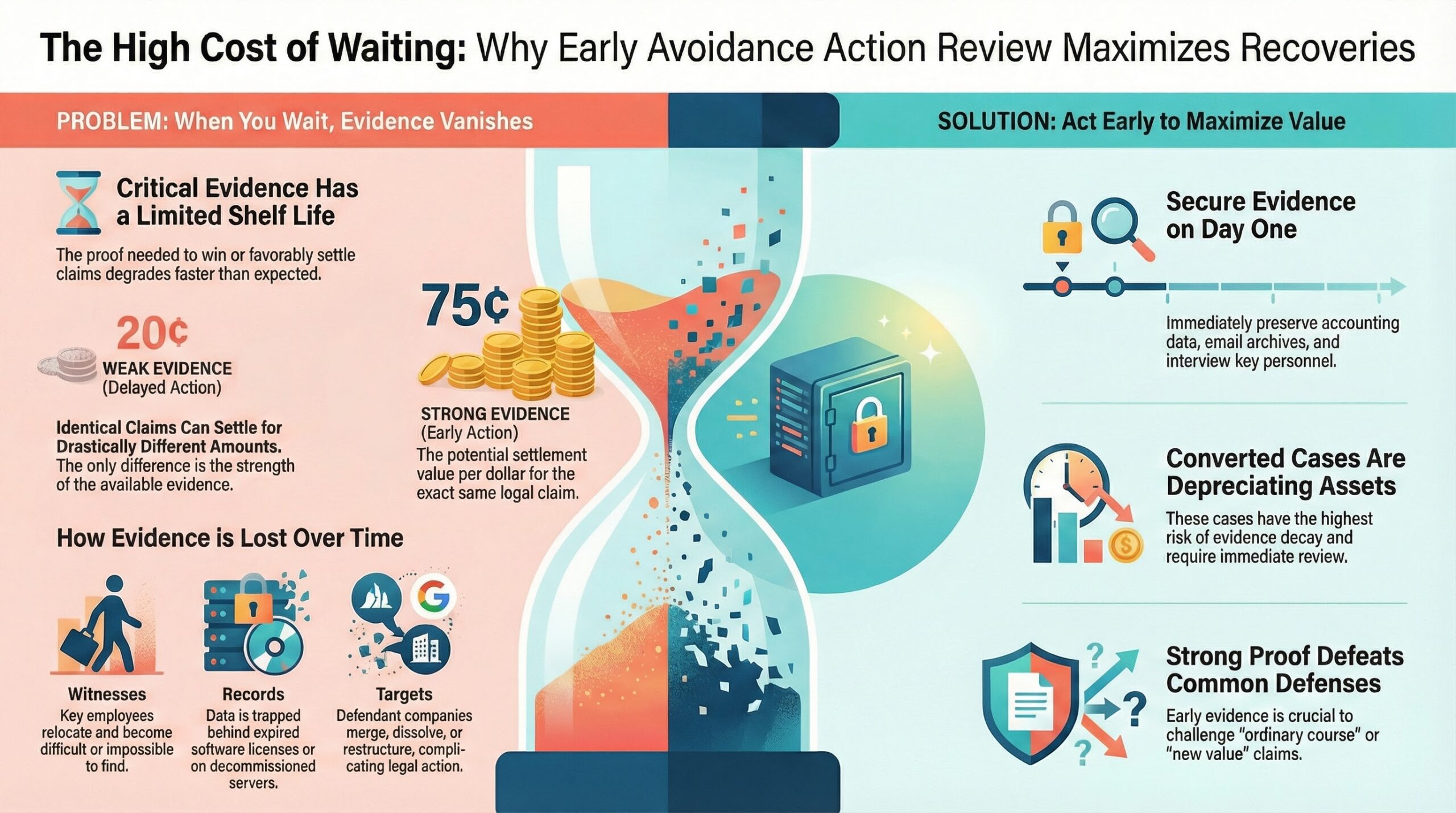

Most avoidance action review happens too late.

Not because trustees are negligent. Not because anyone’s dropping the ball. It happens because the conventional wisdom says to deal with Chapter 5 claims after the estate is largely administered. Handle the urgent stuff first—liquidate assets, resolve secured creditor disputes, manage the day-to-day—then circle back to preferences and fraudulent transfers.

The logic makes sense. The results don’t.

The High Cost of Waiting: Why Early Avoidance Action Review Maximizes Recoveries

What We’ve Seen Happen

Here’s what we’ve observed across hundreds of cases: evidence degrades faster than anyone expects.

Witnesses disappear. Former employees who could testify to payment pressure, collection calls, or changes in credit terms relocate within months of a bankruptcy filing. I remember one case vividly—the debtor’s accounts payable manager was the only person who could explain why certain vendors got paid ahead of others. By the time avoidance actions were seriously evaluated, she’d moved out of state and changed employers twice. Tracking her down added months and thousands of dollars to the litigation. In another case, we never found the key witness at all.

Records become inaccessible. Payment records, email archives, and accounting data that would defeat a new value defense get locked away when legacy software licenses lapse or servers are decommissioned. We’ve seen estates where the debtor’s ERP system data was trapped behind a six-figure licensing fee. The data existed—it just couldn’t be retrieved at any cost that made sense for the recovery.

Transferees restructure. Vendors merge, move, dissolve, or become difficult to locate. A clear target at the petition date may have been acquired eighteen months later, with the preference liability buried in indemnification provisions that turn a straightforward demand into a complicated mess. We recently evaluated a portfolio where three of the top ten preference targets had undergone corporate changes. Just figuring out who to sue added months of investigation.

The pattern is consistent: wait too long, and the evidence you need to maximize recovery simply isn’t there anymore.

Why This Matters for Your Recoveries

I’ll be direct about what this means in dollars.

We’ve seen claims that could have settled for 60-70 cents on the dollar at month three settle for 25-30 cents at month eighteen—same claim, same defendant, same legal theory. The only difference was the evidence available to support the trustee’s position.

That’s not a rounding error. On a $500,000 preference claim, that’s the difference between recovering $325,000 and recovering $137,500. Multiply that across a portfolio, and you’re talking about real money that should have gone to creditors.

The math is straightforward. A preference claim with strong evidentiary support—dunning letters, emails showing collection pressure, testimony from a witness who remembers the relationship—settles for materially more than the same claim where those facts can only be alleged, not proven.

Defendants know the difference. Their counsel knows the difference. Settlement valuations reflect it.

A Story About Ordinary Course

Let me give you a concrete example.

The ordinary course defense under 11 U.S.C. § 547(c)(2) is the most common defense we encounter. To defeat it, you need evidence of pressure—dunning letters, collection calls, threats to place the debtor on COD terms, acceleration of payment timing. Evidence that the debtor wasn’t paying in the normal course but responding to squeeze.

That evidence lives in communications between the debtor and the transferee. Emails from the vendor’s credit department. Notes in the debtor’s accounts payable system. Testimony from the person who decided which vendors got paid and why.

We handled a case last year where the debtor’s AP manager had kept detailed notes on vendor calls. One vendor had threatened to report the debtor to credit agencies and cut off supply unless payment was accelerated. Those notes were devastating to their ordinary course defense. The case settled for 72 cents on the dollar within 60 days of our demand letter.

Around the same time, we took on a similar case—same size claim, same industry, same defense asserted. But the records had been lost when the debtor’s office closed, and the AP manager had moved overseas. We could allege pressure, but we couldn’t prove it. That case settled for 28 cents after extended litigation.

Same legal claim. Same defense. Different evidence. Different outcome.

I think about those two cases often. The legal work was comparable. The difference was timing—when the evidence was secured, and whether it still existed when we needed it.

The Subsequent New Value Problem

We see the same pattern with subsequent new value under § 547(c)(4).

Defendants assert this defense by claiming they shipped goods or provided services after the preferential payment—new value that should offset the preference amount. In theory, it’s straightforward: the transferee gave back value, so the net transfer was less than the gross payment.

In practice, calculating and disputing subsequent new value requires detailed records. What was shipped? When? Was it received? Did the debtor pay for it with a later payment that’s also being avoided?

Early in the case, those records are accessible. The debtor’s system shows what was received. The transferee’s system shows what was shipped. Discrepancies can be identified and used as leverage.

Late in the case, the debtor’s records may be gone. You’re left relying on the transferee’s self-serving calculations. We’ve seen defendants claim new value credits that included goods shipped but never received, returns that were never credited, and shipments outside the preference period entirely. Without the debtor’s records, those claims are difficult to challenge.

It’s frustrating to know a defendant is inflating their new value calculation and not have the records to prove it.

Converted Cases: Where This Matters Most

If there’s one category of cases where early review pays the biggest dividends, it’s converted Chapter 11s.

When a case converts to Chapter 7, the preference period becomes measurable from the original petition date. This can create substantial preference exposure that wasn’t present during the Chapter 11 phase—sometimes millions of dollars in previously unexamined claims.

But converted cases also present the greatest evidentiary risk. By the time conversion occurs, the debtor has often been in bankruptcy for months or years. Employees have scattered. Records have been boxed up, moved, or destroyed. The operational knowledge that would support avoidance claims has dissipated.

In our experience, trustees who evaluate avoidance actions immediately upon conversion—within the first 30-60 days—recover materially more than those who wait. We’ve seen portfolios where early evaluation produced recoveries 40-50% higher than comparable cases where review was deferred.

I don’t say that to be dramatic. It’s just what the numbers show.

The converted Chapter 11 case that lands on your desk today is a depreciating asset. Every month you wait, the evidence supporting recovery becomes harder to obtain.

What We’d Suggest

Front-loading avoidance review doesn’t mean filing complaints on day one. It means conducting diligence early—while the evidence exists—so that when you do pursue claims, you’re negotiating from a position of strength.

Secure records immediately. Upon appointment or conversion, obtain the debtor’s accounting records, email archives, and AP/AR aging reports before systems are shut down. This is table stakes, but it’s easy to defer when other matters feel more urgent.

Identify and interview key witnesses early. The people who managed vendor relationships, made payment decisions, and handled collection calls have information that will determine outcomes. Interview them while they remember—and before they relocate.

Run preliminary preference analysis. Identify the top targets by dollar amount and assess likely defenses based on the records you’ve secured. This doesn’t require deep legal analysis upfront—it requires systematic data review to prioritize where to focus.

Engage special counsel early if you’re going to use them. A firm evaluating claims at month three has access to information that won’t exist at month twelve. We’ve taken over portfolios from prior counsel where the delay alone had materially reduced what we could recover. It’s one of the more frustrating patterns we see.

The Bottom Line

I’ve been doing this work long enough to know that none of this is news to experienced trustees. You’ve seen evidence disappear. You’ve dealt with witnesses who can’t be found. You’ve settled claims for less than they were worth because the proof just wasn’t there.

What I hope is useful is the specificity: the 40-50% recovery differential we’ve observed, the 72 cents versus 28 cents on comparable claims, the pattern of converted cases losing value every month review is deferred.

Early evaluation isn’t about working faster for its own sake. It’s about recognizing that avoidance action evidence has a shelf life—and respecting that reality in how you prioritize your cases.

Key Takeaways

- Evaluate avoidance actions early in the case lifecycle. The “rear-view mirror” approach—waiting until the estate is largely administered—costs real money.

- Converted Chapter 11 cases warrant immediate review. These have the greatest upside and the fastest evidence decay.

- Witnesses and records disappear faster than expected. Former employees relocate. Systems go offline. Data becomes inaccessible.

- The same claim is worth more with strong evidence. We’ve seen 40-50% recovery differences between early and late evaluation of comparable portfolios.

- Timing affects the bottom line. Claims that settle for 70 cents at month three may settle for 28 cents at month eighteen.

Have cases where avoidance actions haven’t been evaluated—or were reviewed late in the process?

We’d welcome the chance to take a look. We routinely take over portfolios from prior counsel and recover on claims others have walked away from.

Contact us for a candid assessment—including whether earlier evaluation would have changed the outcome.